Universal Design: Strategies for Building an Inclusive Learning Experience

A Framework and Strategies for All Learners

Just as physical barriers exist in our physical environment, curricular barriers exist in our instructional environment. Universal Design for Learning, UDL, is the proactive design of a course curriculum to ensure that the content is educationally accessible regardless of learning style, and/or abilities. UDL was first articulated in the 1990s by CAST, and nonprofit education research and development organization. “UDL is a research-based set of principles to guide the design of learning environments that are accessible and effective for all” (www.cast.org). In a way, UDL is the curb cuts to our course content (Rao & Adam, 2011).

The following video provides an excellent overview of UDL. As the video mentions, UDL is “an approach to curriculum that minimizes barriers and maximizes learning for all students.”

The foundation of UDL research, conducted by CAST, indicates three distinct yet inter-related learning networks:

- Recognition Learning Network (the what of learning)

- How we make sense of presented information

- Strategic Learning Network (the how of learning)

- How we demonstrate our learning or mastery

- Affective Learning Network (the why of learning)

- How motivation & participation impacts learning

Before we move forward on specific strategies for creating an inclusive curriculum, I want to be explicit about what UDL is NOT.

- Specialized privileges for a few students

- It is not about special accommodations

- Watering down your academic expectations

- It is not about making courses easier – school is supposed to be challenging if learning occurs

- A “magic bullet” or “fix” for all students

- It is not going to solve all your curricular or pedagogical problems

- A prescriptive formula

- No checklist will offer the “UD solution” for all courses or to meet all student needs

I cannot state enough, there is no one-size-fits-all answer. Additionally, inclusiveness does not mean that all students should be doing the same thing the same way. It means enabling everyone to achieve the same goals through a variety of ways. With that being said, UDL benefits faculty and students! By proactively designing your curriculum using UDL, your teaching becomes more purposeful, structured and systematic. For students, a diverse set of needs are met in the course design – minimizing the need to make special accommodations for students. You naturally increase participation, satisfaction and achievement for ALL Students.

Just like our fingerprints are unique, so too is the way in which we learn. To build inclusive experiences teachers need to consider how their pedagogy, content, and the tools they use impact the unique needs of students. CAST research is at the foundation of three UDL guiding principles. Since we all learn differently, it is essential to offer various ways of learning throughout our curriculum. UDL principles are applied to three distinct areas within our curriculum:

- The Representation of content

- Offer various ways to show essential course concepts in support of the recognition learning networks

- The Demonstration and Expression of learning of the content

- Offer various formats for expression of what the students have learned through strategic learning networks

- The Participation and Engagement of students within the content

- Offer various ways to encourage student engagement in support of affective learning networks

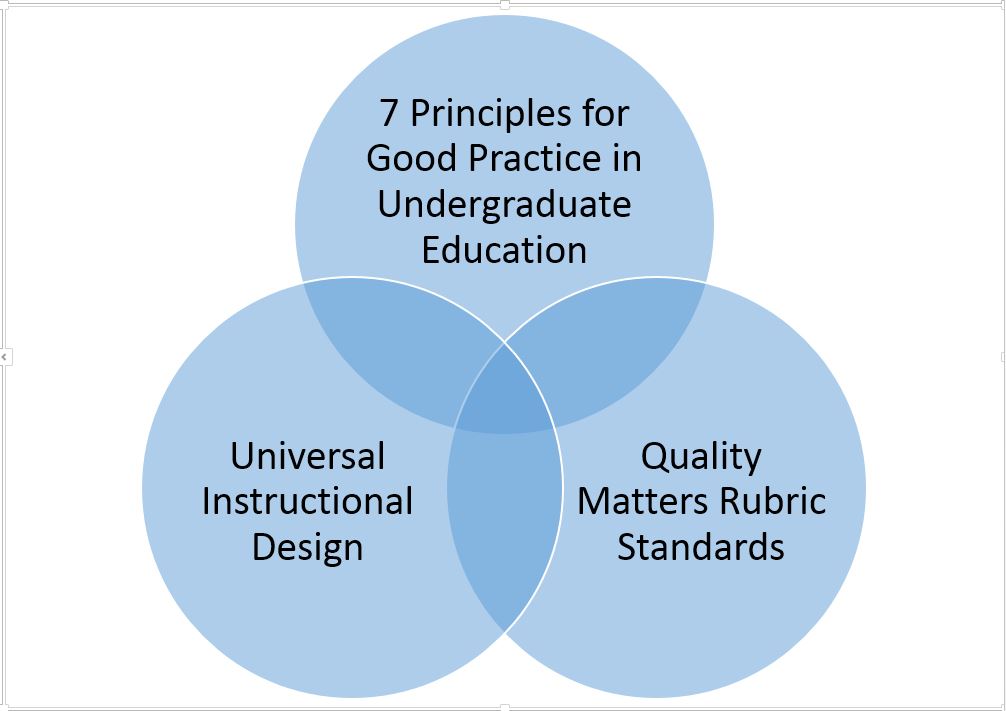

Now that we have reviewed the foundations of UDL, I have created a tool to help us create inclusive curriculum throughout our course. I developed this tool, the UD Checklist, to provide guidance and support to my faculty. This tool merges the principles of Universal Instructional Design (Meyer, 2008), the 7 principles of good practices in undergraduate education (Chickering & Gamson, 1987), and The Quality Matters Rubric, (QM, 2014).

Let’s walk through the 7 Principles for Good Practices in Undergraduate Education together to unpack them and tie them back to the 3 UDL principles. Quality Matters, QM, is woven throughout. You can see QM alignment in the UD Checklist. As a side note, these principles are good for all levels of education; they are not only applicable to “undergraduate” education!

Principle 1: Create a welcoming respectful learning environment (Chickering & Gamson, 1987):

An American Psychological Association study (2009) found that student do not disclose their disability in higher education for many reasons, including fear of not being accepted, fear of discrimination or being stigmatized. Of those that did disclose, “22% said that the response was negative (not accommodating, discriminated against, disbelief on part of staff, and discouraging)” (p. 6)

Providing a welcoming respectful learning environment will help to establish trusting working relationships where students feel comfortable and supported in their learning.

Principle 2: Addressing essential course components (Chickering & Gamson, 1987):

As the architect of your course content, it is essential to ensure that your course learning outcomes align with your course assessments, course learning materials, and course learning activities. Identify what you want your students to be able to do once they complete your course and ensure that you provide ways to practice and accurately measure their learning. One perfect example would be to imagine Stephen Hawking (pictured left), one of the preeminent physicists of our time, taking a timed pencil-and-paper physics exam. He would likely fail it outright. His test performance would not reflect his knowledge of physics – which is extraordinary among the best – but merely his inability to master the means of expression required by a timed paper-and-pencil test.

I always look to Bloom’s Taxonomy when creating course learning outcomes, assessments, and learning activities. Understanding by Design, or Backwards Design, and Action Mapping are lesson planning templates to help you design a well aligned curriculum.

Principle 3: Communicating clear expectations and providing constructive feedback (Chickering & Gamson, 1987):

Instructions and rubrics need to be explicit and thorough. For everything that I provide my students, I make sure the following information is obvious:

- What – what do the students need to do.

- Why – is it clear how this material, activity, assessment aligns with the course learning outcomes? It is helpful to provide an overview of the “why” and/or tie it to the real world.

- Where – where will the students submit their work?

- When – when is the assignment due and when can they expect feedback from me.

It is important that our expectations are explicit both verbally and in writing. Also, naming conventions can lead to confusion if the same name is not used consistently. And finally, it is helpful if large assignments are broken down overtime to allow for draft feedback, peer feedback, and a chance to make improvements, or harness their skills throughout the semester.

Principle 4: Provide natural supports (including technology) for learning to enhance opportunities for all learners (Chickering & Gamson, 1987):

This principle encompasses one of the MOST important things to ensure accessibility and inclusiveness in your course curriculum. Selecting accessible resources, including; textbooks, online resources, and making sure that equivalent alternatives to auditory and visual content is provided. Your course content is at the foundation of your course! If it is not accessible it will be extremely difficult, or nearly impossible, to make changes in a short time frame if needed for specific student accommodations. Alternatively, when our curriculum is accessible, the need for specific accommodations is significantly reduced. If we build our content with accessibility in mind from the beginning, we will minimize barriers and maximize learning for all students (and significantly minimize faculty workload as it is easier to build accessible materials compared to revising completed materials).

Principle 5: Using teaching methods that consider diverse learning styles, abilities, ways of knowing, and previous experience and background knowledge (Chickering & Gamson, 1987):

Knowing that student’s needs and learning styles vary, and that students benefit from, and/or require, information in a variety of formats (including auditory, visual and tactile), consider varying how you express essential course content. Varying the format of your course content increases the likelihood of information access and comprehension and, ultimately, the effectiveness of your instruction. This principle gets to the heart of the first UDL principle.

- Provide various ways to represent essential course concepts. (CAST, nd)

Principle 6: Offering multiple ways for students to demonstrate their knowledge (Chickering & Gamson, 1987):

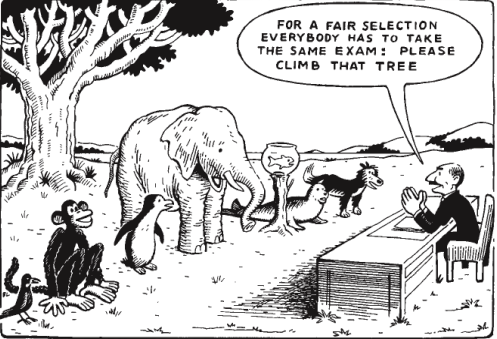

When we focus on measurable goals, we can provide various ways for student to represent their mastery. One size does NOT fit all. Equality does NOT equal fairness. This principle gets to the heart of the second UDL principle.

- Offer students various formats for expression and demonstration of what they have learn. (CAST, nd)

Principle 7: Promote interaction among students and between you and the students (Chickering & Gamson, 1987):

There are three types of active learning interactions in your course; 1) student to instructor, 2) student to content, and 3) student to student. “Active learning entails guiding learners to increasing levels of responsibility for their own learning.” (The Quality Matters Rubric, 2014, p. 22) This principle gets to the heart of the third UDL principle.

Course design is an iterative process that develops over time and should not have to take place in a vacuum. Seek out your institutional resources; Teaching and Learning Centers, Instructional Designers, colleagues and peers. Look to leaders in the field – in addition to CAST, Quality Matters is becoming a leader in setting the standard for quality course content in online and hybrid courses (but I strongly recommend using this resource for all courses that use their online LMS platform to disseminate class content). It is a highly reputable organization that is faculty lead and is grounded in research and best practices. They offer robust faculty development, provide certifications, and conduct – and welcome – ongoing research on course development and pedagogy. It is possible to join as an individual and as an institution. The Ohio QM Consortium is the largest state organization in the nation. Reach out to your administration to find out how you can participate in Quality Matters either nationally or locally, and as an individual or an institution.

Our student body is becoming increasingly diverse, as are their needs. Building inclusive course content is at the heart of student success. Utilizing UDL principles (CAST, nd), the 7 principles of good practices in undergraduate education (Chickering & Gamson, 1987), and The Quality Matters Rubric, (QM, 2014) will minimizes barriers and maximizes learning for all students.

Reference

American Psychological Association (2009). Barriers to Students with Disabilities in Psychology Training. Disability Issues in Psychology. Office Public Interest Directorate. American Psychological Association. Washington DC. Retrieved from: https://www.apa.org/pi/disability/dart/survey-results.pdf

Chickering, A. W. & Gamson, Z., G. (Fall, 1987). 7 Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education. Washington Center News.

Meyer, K. A. (Spring, 2008). Inclusive curricula: Universal Instructional Design. CTE Notebook, 10 (4). Paul C. Reinert Center for Teaching Excellence, Saint Louis University.

Quality Matters Rubric Standards (2014). Retrieved from https://www.qualitymatters.org/rubric

Rao, T & Tanner, A (2011). Curb cuts in cyberspace: Universal Instructional Design for online courses. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability 24 (3), 211 – 229.

Universal Design for Learning. http://www.cast.org/udl/

Tammy Waldron is currently an Instructional Designer at the Christ College of Nursing and Health Sciences in Cincinnati, Ohio. She earned a Master of Education in Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Toledo and a Leadership and Online Learning Endorsement from the University of Cincinnati. Tammy is the Quality Matters (QM) Coordinator at her institution, holds a QM Master Reviewer certificate, and is a APPQMR and IYOC face to face facilitator. For questions about this month’s blog please contact Tammy at: Tammy.Waldron@thechristcollege.edu

|